by George Sidney Hurd

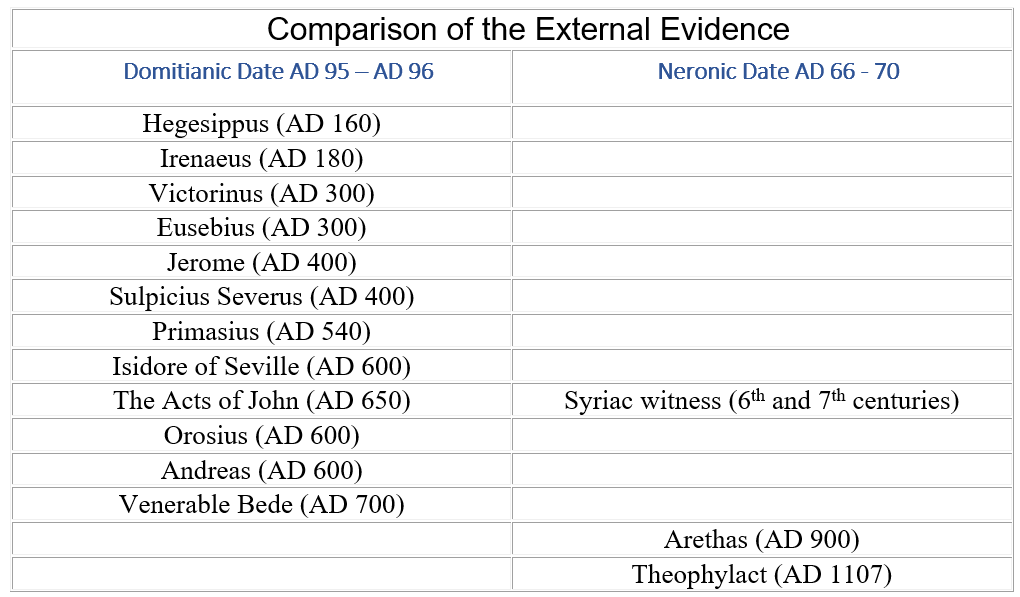

External evidence of the Late Date of Writing in AD 97. Historically, until the 7th century, the Church uniformly believed that the book of Revelation was written after the end of Domitian’s reign between AD 95 and AD 96. For the Futurist, the date in which the book of Revelation was written is of little consequence, since the prophecies are understood to be as yet unfulfilled. However, for the Preterist it is absolutely essential to establish a pre-AD 66 date of writing, since they must argue that the prophecies described therein were, for the most part, fulfilled between AD 66 and AD 70. Preterism stands or falls upon this early date for John’s revelation. Welton, while at the same time, strangely implying that the early dating of Revelation has been the historic position, concedes, saying: “If the book was written in AD 96, as many modern teachers claim, then my point of view cannot be valid.” [1] However, there is no indication that the early Church questioned that the book of Revelation was written at the close of Domitian’s reign in AD 95 – AD 96. This in itself is perhaps one of the greatest arguments against the Preterist case for an early authorship of Revelation. Those closest in time to John and the writing of Revelation, uniformly understood that John wrote the book of Revelation while exiled on the island of Patmos during the time that Domitian was the Emperor of Rome. Below is a time chart demonstrating that the later date, at the close of Domitian’s reign, was universally accepted until well into the Dark Ages.

One of the first and most notable Early Church Fathers who mentions the timing of John’s Revelation is Irenaeus (AD 120 – AD 202), who lived in Smyrna, one of the seven churches specifically addressed in the book of Revelation. He was a disciple of Polycarp (bishop of Smyrna), who in turn, was a disciple of John. Irenaeus, in his fifth book “Against Heresies,” speaks against speculations concerning the name of the future Antichrist:

“We will not, however, incur the risk of pronouncing positively as to the name of Antichrist; for if it were necessary that his name should be distinctly revealed in this present time, it would have been announced by him who beheld the apocalyptic vision. For that was seen no very long time since, but almost in our day, towards the end of Domitian's reign.” [1] In this statement Irenaeus, speaking against premature speculations as to the identity of the Antichrist, appeals to the lack of any mention of the Antichrist’s name in the book of Revelation. In doing so, he mentions something that seems to have been common knowledge at the time. He said that John had received the apocalyptic vision recently: more specifically, towards the end of Domitian’s reign (AD 81 – AD 96). [2] Years later Eusebius, the Church historian, in AD 325, confirmed the credibility of Irenaeus’ testimony. Speaking of the persecution under Domitian, he quotes Irenaeus’ words to confirm the timing of John’s exile on Patmos: “It is said that in this persecution the apostle and evangelist John, who was still alive, was condemned to dwell on the island of Patmos in consequence of his testimony to the divine word. Irenaeus, in the fifth book of his work Against Heresies, where he discusses the number of the name of Antichrist which is given in the so-called Apocalypse of John, speaks as follows concerning him: ‘If it were necessary for his name to be proclaimed openly at the present time, it would have been declared by him who saw the revelation. For it was seen not long ago, but almost in our own generation, at the end of the reign of Domitian.” [3] Eusebius, as a historian, relied heavily upon the testimony of Irenaeus in establishing historical fact, quoting him very frequently. Eusebius is revered as a great Church historian, giving an accurate account of the first centuries of the Church. He faithfully presents the Early Church Fathers’ belief in a future fulfillment of apocalyptic prophecies. Preterism was unknown at that time and therefore there was no need to establish an early date for Revelation, or to argue that Nero was the Beast, or deny that the Beast of Revelation is referring to the future Antichrist. Not surprisingly, the first person on record to have called into question the reliability of Irenaeus’ testimony was Jakob Wettstein in 1752, who was himself a Preterist. [4] There is another very early Church Father, Hegesippus (AD 110 - AD 190), whom Eusebius also quotes, confirming the AD 96 date for Revelation. Hegesippus even predates Irenaeus by some 30 years. Eusebius constantly made reference to the Memoirs of Hegesippus. At one point he says: “Hegesippus in the five books of Memoirs which have come down to us has left a most complete record of his own views.” [5] Although only a few fragments of his Memoirs remain to this day, Eusebius apparently draws from his Memoirs when he says: “But after Domitian had reigned fifteen years, and Nerva had succeeded to the empire, the Roman Senate, according to the writers that record the history of those days, voted that Domitian's honors should be cancelled, and that those who had been unjustly banished should return to their homes and have their property restored to them. It was at this time that the apostle John returned from his banishment in the island and took up his abode at Ephesus, according to an ancient Christian tradition.” [6] The immediate context of this statement indicates that Hegesippus was at least included in those whom Eusebius referred to when he says: “according to an ancient Christian tradition.” In the immediate context we can see that Eusebius apparently had before him the Memoirs of Hegesippus as he wrote concerning John’s release after Domitian’s reign. Just eight verses earlier, Eusebius indicates that he is drawing upon his Memoirs: “These things are related by Hegesippus.” [7] Then again just two verses before the above quote he says: “These things are related by Hegesippus.” [8] Therefore, it is more than likely that Eusebius was referring to the Memoirs of Hegesippus in the above quote. In any case, Eusebius makes it clear that in his day it was “ancient Christian tradition” that the time of John’s exile was during Domitian’s reign in the AD 90s. Nowhere in any early writings, that record the history of those days, is there any indication that John was exiled by Nero in the AD 60s. In addition to the testimony of Irenaeus and Hegesippus, which are also corroborated by Eusebius, there were other early writings confirming the AD 96 date, as can be seen on the chart above. One other source worthy of note is Victorinius, who wrote the oldest commentary on Revelation in existence, written in AD 258. Commenting on chapter 10 of Revelation, he says the following concerning John’s exile: “He says, ‘It is necessary to preach again,’ that is, to prophesy, ‘among peoples, tongues, and nations:’ this is because, when John saw this, he was in the island of Patmos, condemned to a mine by Caesar Domitian. Therefore, John is seen to have written the Apocalypse there. And when now old, he thought it possible to return after the suffering. Domitian having been killed, all his judgments were undone and John was released from the mine, and thus afterward he handed over this same Apocalypse which he received from the Lord. This is: ‘It is necessary to preach again’.” [9] Jerome (AD 347 – AD 420) also, in two separate volumes, places the context of John’s visions as having been received during the time of Domitian’s rule: “For he saw in the island of Patmos, to which he had been banished by the Emperor Domitian as a martyr for the Lord, an Apocalypse containing the boundless mysteries of the future.” [10] “In the fourteenth year then after Nero, Domitian having raised a second persecution, he was banished to the island of Patmos, and wrote the Apocalypse on which Justin Martyr and Irenaeus afterwards wrote commentaries. But Domitian having been put to death and his acts, on account of his excessive cruelty, having been annulled by the senate, he returned to Ephesus under Pertinax and continuing there until the time of the emperor Trajan, founded and built churches throughout all Asia, and, worn out by old age, died in the sixty-eighth year after our Lord’s passion and was buried near the same city.” [11] Another early Church historian, Sulpitius Severus, a contemporary of Jerome, (AD 360 – AD 420) also bears witness that, in their time, the Domitian date of the book of Revelation was still unquestioned: “Then, after an interval, Domitian, the son of Vespasian, persecuted the Christians. At this date, he banished John the Apostle and Evangelist to the island of Patmos. There he, secret mysteries having been revealed to him, wrote and published his book of the holy Revelation, which indeed is either foolishly or impiously not accepted by many.” [12] Welton sweeps aside all the testimonies presented above indicating the AD 96 date for the writing of the book of Revelation in favor of one solitary statement, written in the introductory page to the book of Revelation in the Syriac Peshitta Version of the Bible, which claims that Nero was the emperor that exiled John to Patmos. Based solely upon this single source as external evidence, he concludes the following: “Nero Caesar ruled over the Roman Empire from AD 54 to AD 68. Therefore, John had to have been on the island of Patmos during this earlier period. One of the oldest versions of the Bible tells us when Revelation was written! That alone is a very compelling argument.” [13] Welton gives greater weight to this introductory note in the Syriac version than to all of the early testimonies supporting a later AD 96 date, saying that the Peshitta dates back to the second century. What he fails to see, or chooses not to point out, is that the second century version excluded certain books of the New Testament, including the book of Revelation. The book of Revelation wasn’t included in the Peshitta Version until AD 616. [14] The earliest Aramaic manuscript in existence which contains the book of Revelation, is known as the Crawford Aramaic New Testament manuscript, dating back to the twelfth century. [15] Today, we have no way of knowing when the introductory note was added to the Aramaic text of Revelation for the first time. The earliest would be in AD 616 and it could well have been added much later. This late addition to the Peshitta can hardly be said to be a very compelling argument for the early date of writing of the book of Revelation. Although Welton says that there are other historical documents which tell us that John was exiled during Nero’s reign, he only cites this one solitary example. The fact is that there are no early documents supporting the early date for Revelation. All arguments drawn for support from other sources are dubious at best, and a mere grabbing for straws. The only period in the history of the Church in which the early date became prominent was from 1850 to 1900. Preterists often cite preachers from that period in support of the Preterist interpretation. However most scholars at that time were not Preterists and dated the writing of Revelation after the death of Nero on June 9, AD 68, which would not fit the preterist model, since Nero, who committed suicide in AD 68, is understood by them to be the Beast described in Revelation and also it would put the writing of Revelation in the middle of their three and a half year period of Jerusalem’s destruction. Another external indication that favors the later AD 96 date for the book of Revelation is that Domitian was known to exile Christians, as opposed to executing them, as was the case with Nero. Peter and Paul were executed by Nero, whereas Christians under the reign of Domitian were commonly exiled. Eusebius speaks of Domitian’s practice of banishing Christians: “And they, indeed, accurately indicated the time. For they recorded that in the fifteenth year of Domitian, Flavia Domitilla, daughter of a sister of Flavius Clement, who at that time was one of the consuls of Rome, was exiled with many others to the island of Pontia in consequence of testimony borne to Christ.” [16] Domitian’s practice of banishment is also corroborated by a reliable secular historian, although John is not mentioned by name. Dio Cassius (AD 155 – AD 235), a Roman historian who was also admitted to the Roman senate in AD 180 and was placed over Pergamum and Smyrna, wrote an eighty volume Roman History. Three times in his work he makes reference to Domitian’s practice of exiling prisoners. He also mentions the release of exiles immediately after his death. [17] So, even secular history of that day corroborates the early Church’s account, placing the time of John’s exile to the island of Patmos under Domitian’s rule. Therefore, we can clearly see that all external evidence uniformly supports the later date of AD 96 for the writing of the book of Revelation. Indeed, there is nothing even worthy of consideration that can be presented in favor of an early, AD 66 date. An annotation in the introduction to a late Syrian translation of the book of Revelation, which is a twelfth century manuscript copy, can hardly be considered to be of any value for determining the date in which Revelation was written. Most scholars would agree that there is no evidence for the early date of writing even worthy of consideration in all of Church history. For brevity I will only cite B.W. Johnson’s conclusion: “It is thus seen that the array of testimony to the date of Domitian’s reign is so strong as to leave no doubt, except where persons are compelled by their theories of interpretation to assume that John wrote in the reign of Nero.” [18] We can now turn our attention to the internal evidences within the contents of the book of Revelation itself which argue for a later date of writing. Internal Evidence that Revelation was written in AD 96. The internal interpretive evidence in support for the post-AD 70 futuristic fulfillment of the prophecies of Revelation will be demonstrated in the next chapter. Here we will be considering the circumstantial evidence for the late AD 96 date of writing. The church of Smyrna didn’t exist in AD 70. One of the seven churches Jesus addressed in the first three chapters of Revelation was the church of Smyrna (Rev 2:8-11). Polycarp, writing to the Philippians in AD 110, states that those living in Smyrna during the ministry of Paul had not yet heard the gospel: “For he (Paul) boasts of you (Philippians) in all those Churches which alone then knew the Lord; but we, of Smyrna, had not yet known Him.” [19] This statement made by Polycarp in AD 110 is corroborated in the book of Acts and the epistles of Paul since Smyrna is mentioned neither in Acts nor in the epistles. After Paul’s first imprisonment in Rome, he was released and continued his missionary journeys for a few months until the following year when Rome was burned in AD 64. During his time of freedom, he wrote 1 Timothy and Titus. He was imprisoned a second time in Rome and finally beheaded in AD 66. During his final imprisonment he wrote 2 Timothy. However, in none of his epistles does he make mention of Smyrna. The lack of any mention of Smyrna confirms what Polycarp said. Therefore, the church of Smyrna to whom Jesus spoke in Revelation didn’t even exist in AD 70, and therefore the book of Revelation is not applicable to the time between AD 66 and AD 70. The Church of Laodicea was flourishing in the AD 60s, but Spiritually Impoverished in Revelation 3. Paul mentions the church of Laodicea in the epistle of Colossians which was written around AD 62 (Col. 2:1-2; 4:13,16). At that time, it appears to have been a healthy, thriving church. However, when Jesus addresses the Laodiceans in Revelation 3:14-22, He rebukes them for their apathy. He gives them the most lengthy and severe rebuke of all the seven churches. Apart from reaffirming His love and faithfulness towards them, He doesn’t have anything positive to say to them. It is unlikely that the church in Laodicea would have undergone such a drastic spiritual decline in just a couple of years. Also, Jesus speaks of them as being rich and prosperous and in need of nothing. Laodicea was devastated by an earthquake in AD 60, which left them impoverished and in ruins. [20] The devastation was so great that it took them 30 years to rebuild. [21] It is highly unlikely that the church in Laodicea was experiencing great wealth and prosperity in the AD 60s while their city was still in ruins. Therefore, we have seen that the early date of writing of the book of Revelation not only lacks any significant external evidence, but also we can see from the internal circumstantial evidence that the Letters to the seven churches had to have been written later than the AD 60s, since the church of Smyrna didn’t yet exist and the church of Laodicea was still a spiritually thriving church in the AD 60s. There is no concrete objective evidence whatsoever which the Preterists can reasonably present in support of the early date of writing - either internally or externally. For a more in-depth presentation of the arguments for a late AD 95 – AD 96 date for the writing of Revelation, I highly recommend Mark Hitchcock’s dissertation: “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation. [22] In the following chapter we will consider what Preterists present as interpretive evidences within the book of Revelation itself. Obviously, interpretive evidence is by its very nature subjective and depends upon the perspective of the interpreter. From the very outset it should be kept in mind that their interpretations have no credence whatsoever, since their subjective interpretations fly in the face of all objective internal and external evidence indicating a late date of writing - twenty-five years after their AD 66 – AD 70 timeframe for the fulfillment of the prophecies of Revelation. This blog is an excerpt from my book: “Last Days – Past or Present?” [1] Welton, Jonathan (2013-11-01). Raptureless: An Optimistic Guide to the End of the World - Revised Edition Including The Art of Revelation (Kindle Location 4446). BookBaby. Kindle Edition. [2] Irenaeus, Book 5, Chapter 30, section 3. [3] Irenaeus not only pinpoints the timing of John’s visions on Patmos to AD 95 - 96. He also makes it clear that the Beast of Revelation was understood to be the Antichrist and that, he was yet to come and his identity was yet unknown to the Church in his time. [4] Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series 2, Volume 1, section 5. [5] Hitchcock, Mark. “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary. December 2005. p. 28. http://www.pre-trib.org/data/pdf/hitchcock-dissertation.pdf [6] Eusebius, Book 4, Chapter 22, section 1. [7] Eusebius, Book 3 Chapter 20. section 10. [8] Eusebius, Book 3, Chapter 19. [9] Eusebius, Book 3, Chapter 20, section 8. [10] St. Victorinus, Commentary on Revelation, Chapter 10. [11] Jerome, Against Jovinianus, book one, §26. [12] Jerome, Lives of Illustrious Men, Chapter 9, section 6,7. [13] Sulpitius Severus, The Sacred History, Book 2, Chapter 31. [14] Welton, Jonathan (2013-11-01). Raptureless: An Optimistic Guide to the End of the World - Revised Edition Including The Art of Revelation (Kindle Locations 4458-4459). BookBaby. Kindle Edition. [15] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peshitta. [16] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crawford_Aramaic_New_Testament_manuscript. [17] Eusebius, Book 3, Chapter 18, section 5. [18] Hitchcock, Mark. “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary. December 2005. p. 54. http://www.pre-trib.org/data/pdf/hitchcock-dissertation.pdf [19] Johnson, B.W. A Vision of the Ages, p. 19. [20] Polycarp, Epistle to the Philippians, Chapter 11. [21] Tacitus Annals 14:27:1. [22] Hitchcock, Mark. “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary. December 2005. p. 187. http://www.pre-trib.org/data/pdf/hitchcock-dissertation.pdf [23] Hitchcock, Mark. “A Defense of the Domitianic Date of the Book of Revelation.” Dissertation for Dallas Theological Seminary. December 2005. http://www.pre-trib.org/data/pdf/hitchcock-dissertation.pdf

13 Comments

9/8/2021 06:04:05 am

I actually support an even later date for the Book's Authorship, feeling like it was most likely written during the Reign of Hadrian. I wrote about it on my Prophecy Blog last year.

Reply

James D

2/6/2022 06:40:29 am

Too many incorrect assertions in this post.

Reply

James D

2/6/2022 08:26:18 am

Yes. It's simply not true that the late date was the only one known until the seventh century.

Reply

James D

2/6/2022 08:34:20 am

The Syriac History of John (written sometime between the 4th and 6th century) places John's exile in Nero's reign also.

Reply

2/6/2022 04:14:30 pm

If you could give me some specific quotes from those sources, I would appreciate it. Before writing my book on the subject I tried to confirm the other purported sources for an early date of Revelation, but didn’t find anything concrete or substantial.

Reply

James D

2/6/2022 06:50:38 pm

A few other comments:

Reply

James D

2/6/2022 06:55:05 pm

That should read "his banishment of actors" not "of acts."

James D

2/6/2022 06:23:16 pm

I can give you some resources that contain all that information, if that helps.

Reply

2/7/2022 02:15:27 am

When the Muratorian fragment says that “Paul, following the example of his predecessor John, writes by name to only seven churches in the following sequence: To the Corinthians first, to the Ephesians second, to the Philippians third, to the Colossians fourth, to the Galatians fifth, to the Thessalonians sixth, to the Romans seventh,” it should not be mistaken as saying that John’s letters to the seven churches preceded in time the epistles of Paul, but simply that Paul, the last to be called as an Apostle, wrote to seven churches, just like his predecessor John did. This is an example of what I mean in my blog when I say that every attempt of Preterists to demonstrate an early date for Revelation is a grabbing for straws at best, while at the same seeking to discredit the weight of evidence against them.

Reply

James D

2/7/2022 04:25:27 am

You can't be following the example of someone else unless they have already done it first. Paul was following John's example when he wrote to seven churches.

Reply

2/7/2022 05:14:14 am

To me, a small delapitated fragment that textual scholars said they couldn't descipher with certainty, isn't sufficient to justify rejecting the multiple early sources confirming the late date. To say, "following the example of" most probably refers to a simple comparison of the similarities between the two rather than literally meaning that that Paul subsequently imitated John's style.

Reply

James D

2/7/2022 07:30:59 am

That particular sentence is preserved in other related texts that don't have the poor quality of Latin like that in the Muratorian Canon. A similar statement is also in a Coptic text. You can find all thisl in the dissertation I linked to, if you're interested.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories______________

The Inerrency of Scripture

The Love of God

The Fear of the Lord

The Question of Evil

Understanding the Atonement

Homosexuality and the Bible

Reincarnationism

Open Theism

Answers to Objections:Has God Rejected Israel:

God's Glorious Plan for the Ages

The Manifest Sons of God

The Trinity and the Deity of Christ

Eternal Preexistence of Christ

Preterism vs. Futurism

The Two-Gospel Doctrine Examined

|